Category: Languages

-

From one API to another: Using ORDS Auto-REST to update a table

I think in this new age of AI/LLMs it is important to understand prompting. Eventually, whether we like it or not, we’ll all need to become “prompt engineers.” And as you’ll see in that thread, you actually have to know what you are doing to be able to ask the right questions and to challenge…

Written by

-

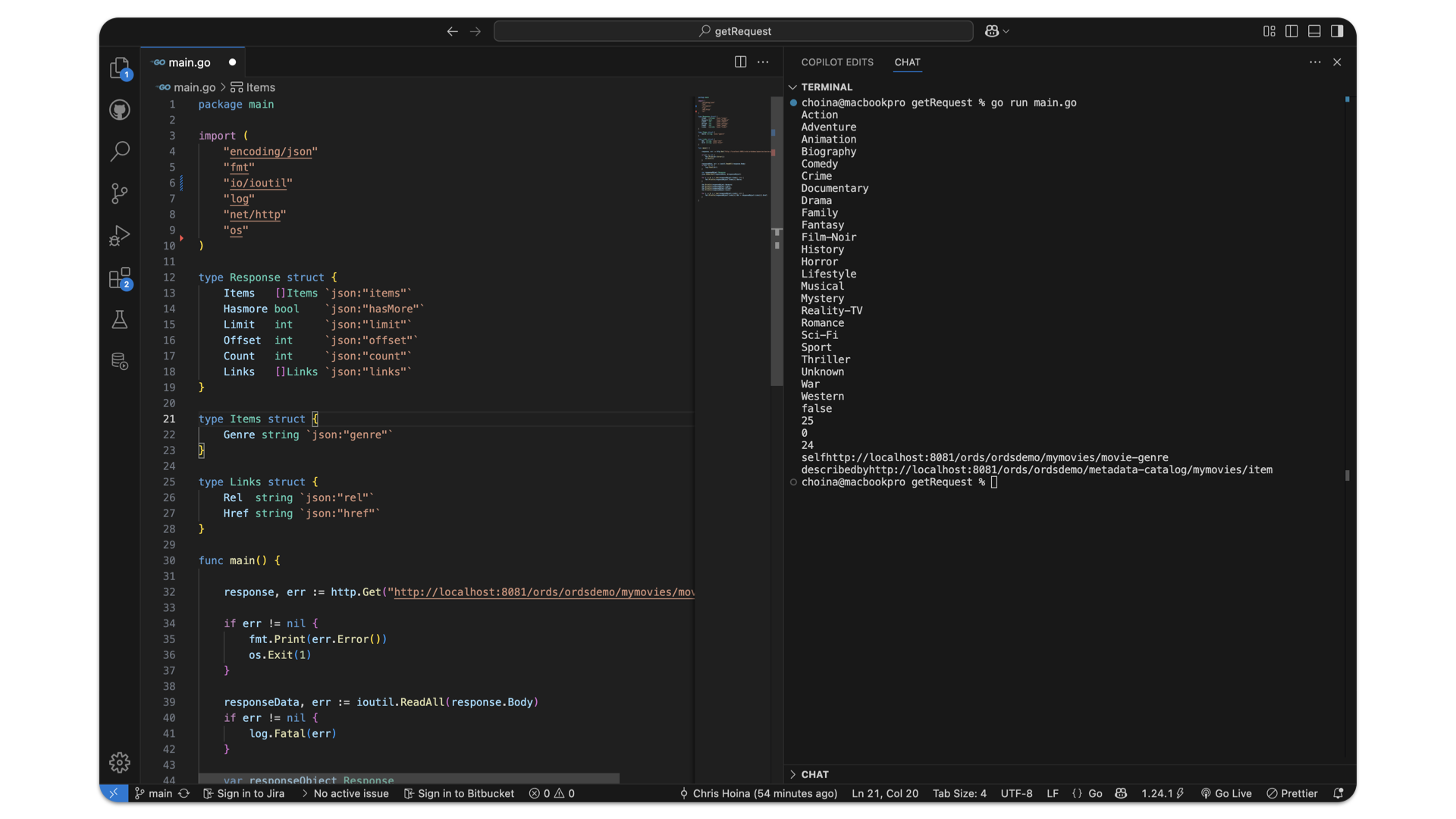

A simple ORDS GET request using the Go language

Venkata this one’s for you 😀 It took me the rest of the afternoon, but here is a pretty simple GET request example, using a user-defined ORDS API. This API is derived from one of our LiveLabs, a Python + JavaScript application. But this particular scenario pretty well exemplifies what we discussed in our presentation…

Written by

-

Random Access Memories: ORDS and JWTs

EXTRA EXTRA! ORDS now supports JSON Web Tokens (JWTs). You can find most of the details in the OAuth PL/SQL Package Reference chapter of the ORDS Developer’s Guide. ORDS JWT OAUTH parameters You’ll notice two new procedures in that package: OAUTH.CREATE_JWT_PROFILE and OAUTH.DELETE_JWT_PROFILE. After getting acquainted with them, I wanted to highlight three parameters of…

Written by

-

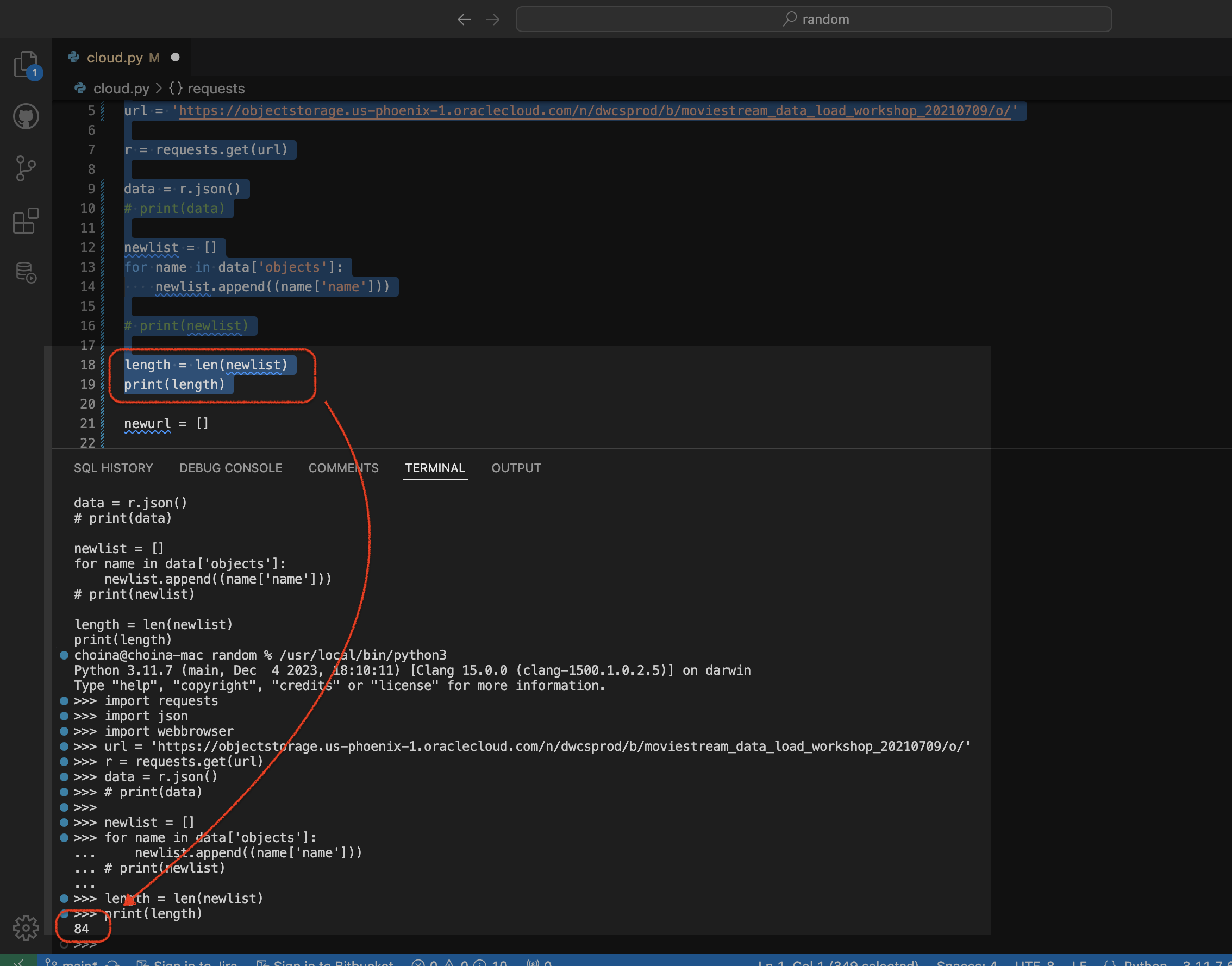

Python script to retrieve objects from Oracle Cloud Bucket

For…reasons, I needed a way to retrieve all the .CSV files in a regional bucket in Oracle Cloud Object Storage, located at this address: https://objectstorage.us-phoenix-1.oraclecloud.com/n/dwcsprod/b/moviestream_data_load_workshop_20210709/o You can visit it; we use it for one of our LiveLabs (this one), so I’m sure it will stay live for a while 😘. Once there, you’ll see all…

Written by

-

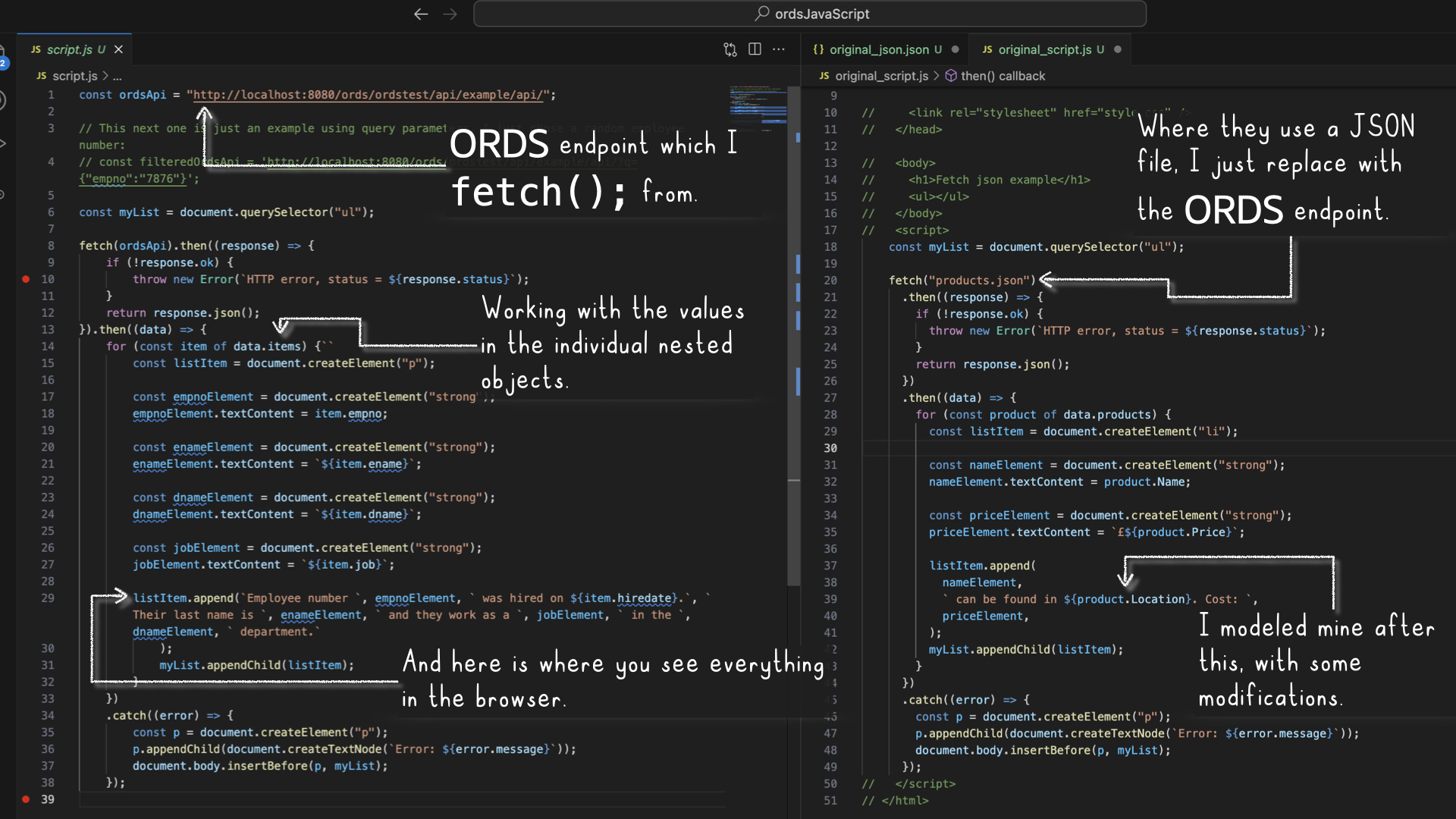

Build an ORDS API Resource Module, GET request with JavaScript fetch, display in HTML

Really trying to optimize SEO with that title 👆🏼! Recap 💡 All the code you’ll see in this post can be found in my moviestreamjs github repository.💡 This post is a continuation of a previous one, which can be found here. In this post, I’ll: If you are coming from the previous related post, then…

Written by

-

ORDS, JavaScript, the Fetch API, and HTML

I found JavaScript and HTML code here and here and “remixed” it to work with one of my sample ORDS APIs. Here is the result: Impressive, no? Care to try it out? Read on friend! References I’ll front load with all the necessary stuff. That way, you can bounce if you don’t feel like reading.…

Written by

-

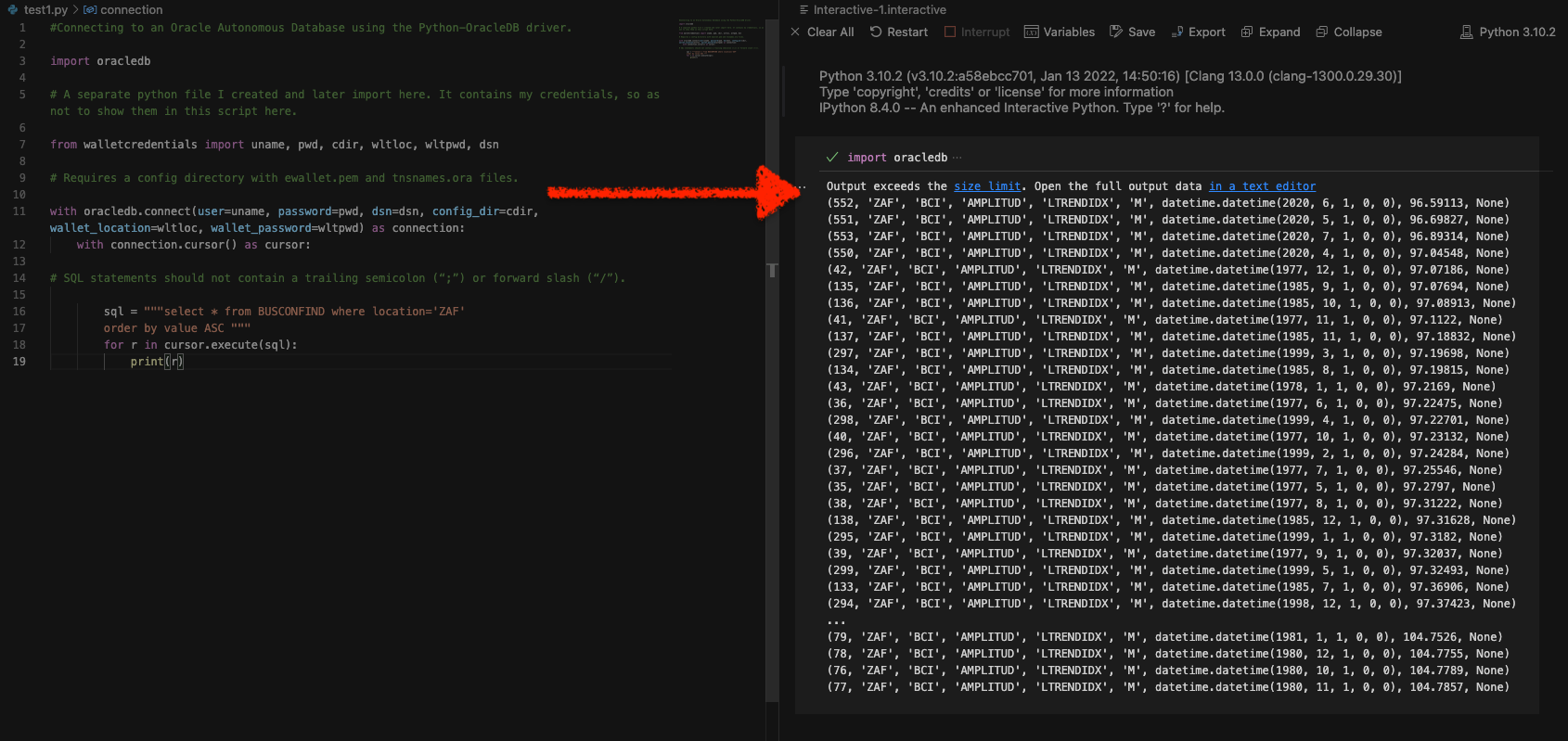

Python and the Oracle Autonomous Database: Three Ways to Connect

Watch the deep dive videos: Part I Part II Part III Welcome back I finally had a break in my PM duties to share a small afternoon project [I started a few weeks ago]. I challenged myself to a brief Python coding exercise. I wanted to develop some code that allowed me to connect to…

Written by

-

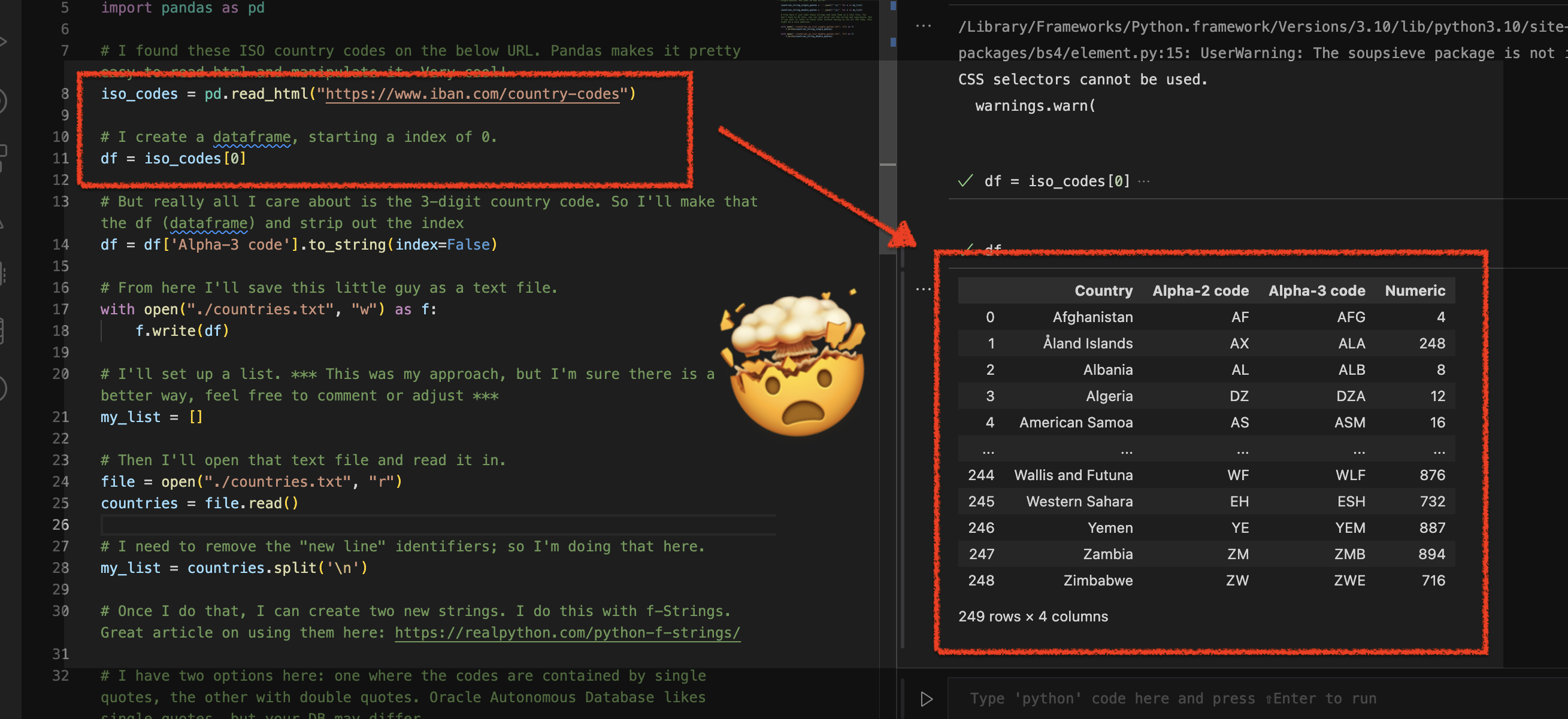

Using Python Pandas to turn ISO Country Codes into a string to use as values for a SQL Query

Summary, code, resources Problem While querying a table (based on this dataset) with SQL, you realize one of your columns uses 3-character ISO Country Codes. However, some of these 3-character codes aren’t countries but geographical regions or groups of countries, in addition to the actual country codes. How can you filter out rows so you are left…

Written by

-

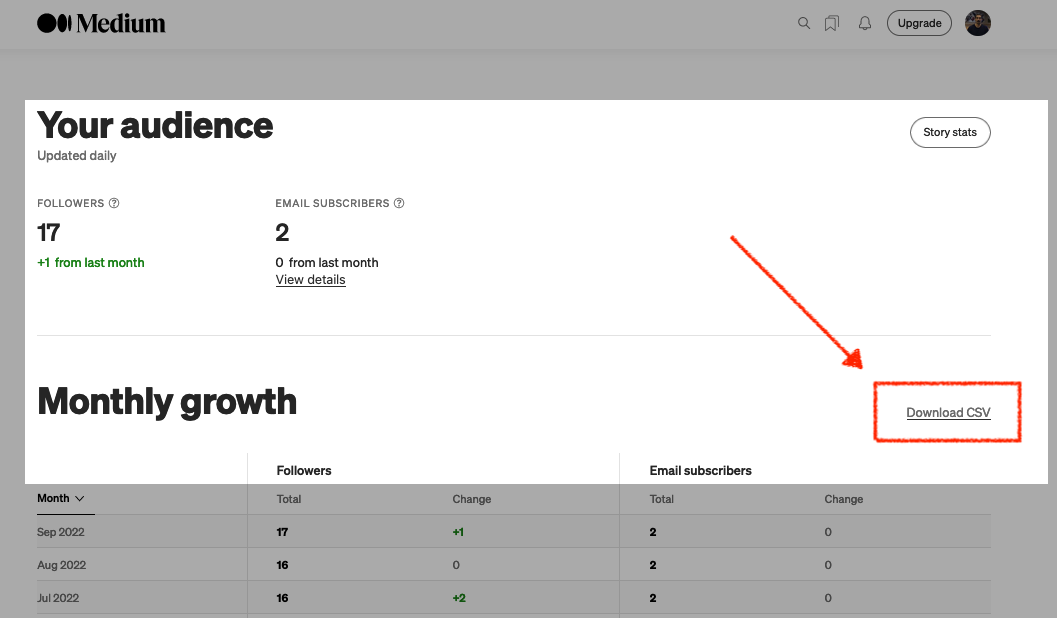

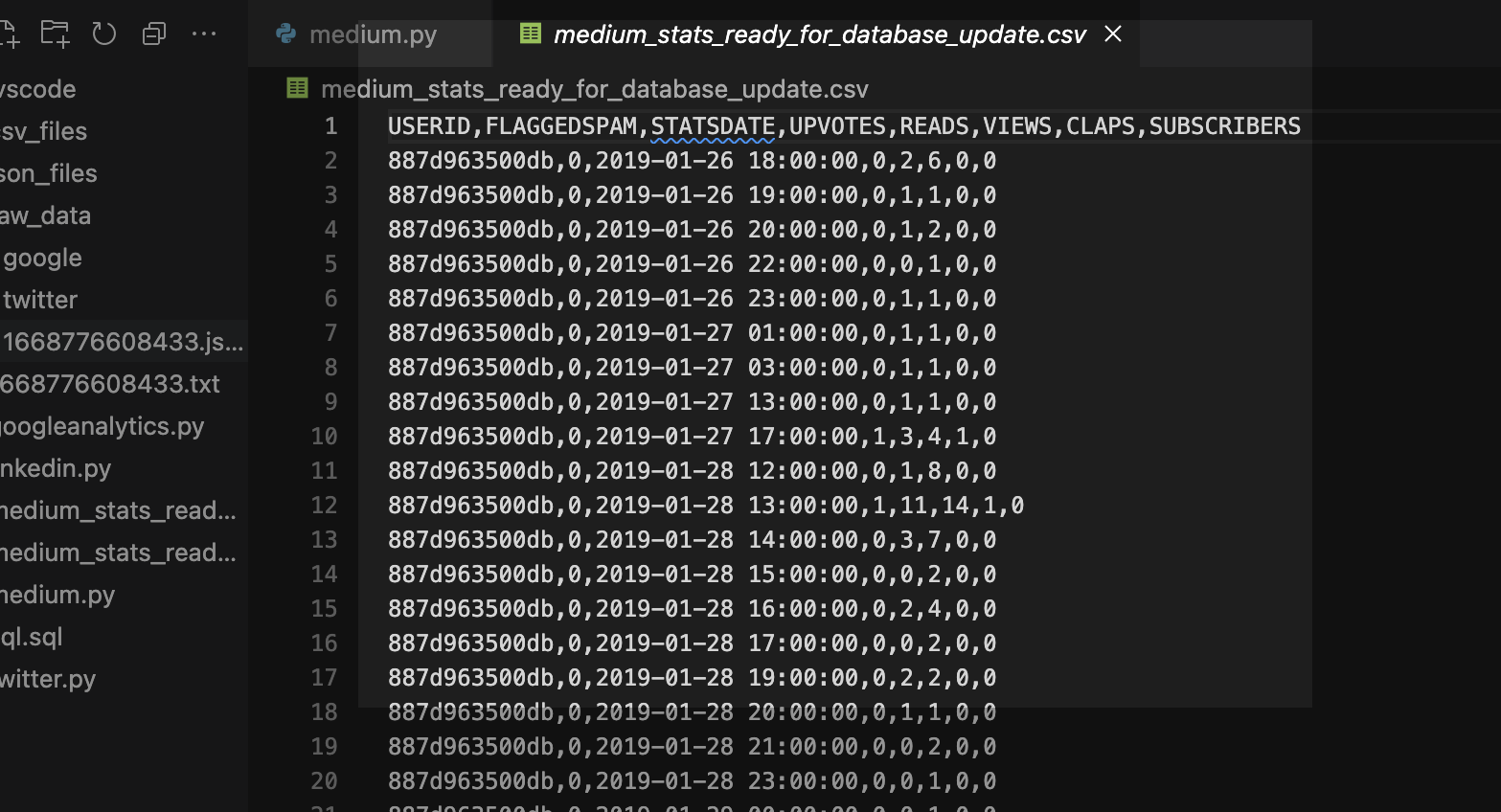

More fun with Medium story stats, JSON, Python, Pandas, and Oracle SQL Developer Web

That’s right; I’m back again for yet another installment of this ongoing series dedicated to working with Medium.com story stats. I first introduced this topic in a previous post. Maybe you saw it. If not, you can find it here. Recap My end goal was to gather all story stats from my Medium account and…

Written by

-

Fun with Python GET requests, Medium stats, and the Oracle Autonomous Database

I feel so silly for posting this because you’ll quickly realize that I will have to leave things unfinished for now. But I was so excited that I got something to work, that I had to share! If you’ve been following along, you know you can always find me here. But I do try my best…

Written by